This is the 2nd post in my series about curriculum in RE and how I think that there are different components to an effective RE curriculum.

Whilst planning this blog, the brilliant Wayne Buisst shared a blog on hinterland which is an excellent contribution to the knowledge in RE conversation. Other than this, I’m not aware of any other public discussions of core/hinterland in RE. Please do link me to any.

What are core and hinterland knowledge?

Put simply core knowledge is what we want students to learn. The key ideas, terms, facts, beliefs, practices etc They are core to a curriculum because they are the parts that make a wider narrative, which once learnt, makes the whole curriculum. They are the curriculum, broken down. They are organised into schemes or topics or units, each with its own important knowledge.

Hinterland knowledge is a term coined by Christine Counsell. It is knowledge that is used to help access, understand and enrich the core. Christine clarifies “The term ‘hinterland’ is as fertile in curricular thinking as its literal meaning. It’s not clutter. This is nothing to do with fun stuff to make things more interesting or engaging, nothing to do with extraneous activities to ‘engage’….”.

How this applies in RE

Stories as hinterland

In RE, hinterland can be found in the ways in which we help students to understand key ideas. For example, one of our most powerful tools is using story. Stories can be hinterland because, whilst knowledge of the story itself, may not be core, the story helps students to understand why that knowledge is important.

Humans love a story and in RE, most religions and beliefs have stories that can help students to remember and understand important knowledge. They are a powerful way to explore key concepts (next blog!).

Stories help transform the abstract into something a child may be able to understand. For example if my core knowledge for a lesson is beliefs about forgiveness in Christianity, we might read the Parable of the Prodigal Son. An interpretation is that the ‘Father’ welcomes the son back regardless of how low he has fallen, representing God and sinners. However I will emphasise other important parts of the story that also help understand forgiveness but also other key ideas e.g. the fact the son worked with pigs (representing uncleanliness – both physical and spiritual).

Experiences as hinterland

We know that students experiencing things can help with understanding and remembering more. Visits, visitors and using artefacts can all contribute to the core but especially the hinterland.

For example, this week I showed my students a chauri when teaching about the importance of the Guru Granth Sahib to Sikhs. As usual they are fascinated by it and what it is. However, in this case I want them to remember why the Guru Granth Sahib is important not that a chauri is usually made from horse hair.

Their experience of seeing something ‘in real life’ is an important aspect of RE which can be tricky for teachers. If we don’t include these experiences then religion and belief becomes abstract or intangible. However these experiences can be the things that are least available to us but can have significant impact on learning. (Tip if you’re trying to find places to visit or people to speak then take a look at the REhubs website and if you’re looking for artefacts I’ve collated a list of possible sources here)

The relationship between the core and hinterland

I think that knowledge in itself isn’t core or hinterland. It is decided by the purpose of a unit as to which it is. In one unit some content could be core but in another unit it might be hinterland, and vice versa. The best hinterland (and indeed core) knowledge can be used at multiple times through a curriculum. It saves time whilst repetition and reapplication help with learning.

For example, I might be teaching students about the Christian idea of sin, and will read the story of the adulterous woman, about to be stoned. Jesus said to those about to stone her ‘Let he who is without sin cast the first stone’. We can then discuss what the story tells Christians about sin. They have an example from the Bible and a reference to a source of wisdom and authority that they can use in their work. However, I know that later in the curriculum we will be learning about the death penalty and adultery. This story is a perfect one for multi-use. However, in its initial telling the core is ‘sin’ and the rest is hinterland. When I come to teach the death penalty I can ask students to recall this story and we can discuss what this might mean about Christian attitudes to the death penalty and how to treat those that that committed adultery; the previous hinterland becomes core. I’m not saying that there was any intention from Jesus of these being separate things but for the sake of learning, the emphasis shifts.

When hinterland goes wrong

If students come away from a lesson and all they remember is the hinterland knowledge then there is an issue. The hinterland should act as a support for the core, which whilst should be remembered, is not the key point of learning. We have to be careful in how we present the hinterland to ensure the right things are remembered!

Examples of hinterland gone wrong:

- Students watching a video animation of Jesus and worrying about things the animator has done – ‘why has that person got a blue bag?’

- Having a visitor speak to students about their beliefs but as part of the intro tells them about themselves e.g. ‘I like dogs not cats’, and students then discussing this point more than the beliefs

- Students remember the date of something important because you taught them a fun way to remember it but can’t remember what happened on the date!

- An example of this in my teaching is using Stormzy’s ‘Blinded by your grace’ song to help explain salvation by grace and they just remember Stormzy and not the Christian teaching of grace!

Sometimes we have to have a careful balance of what we allow to be used as hinterland and how we balance it with core. This is the skill of the good RE teacher.

Why does this matter?

It is important because as think about what it is that we want students to learn, we need to be clear on the exact knowledge we want them to learn.

Core and hinterland contribute to the curriculum as part of a bigger narrative. Alongside the other elements of the curriculum, knowledge should build over time. Some of what we teach now should pop up again later on and provide links between topics. This is why ‘lifting’ a scheme from someone else or online without thinking how the knowledge connects is problematic. A curriculum is not a set of individual schemes/topics. It is a series that has connections and links, where knowledge accumulates.

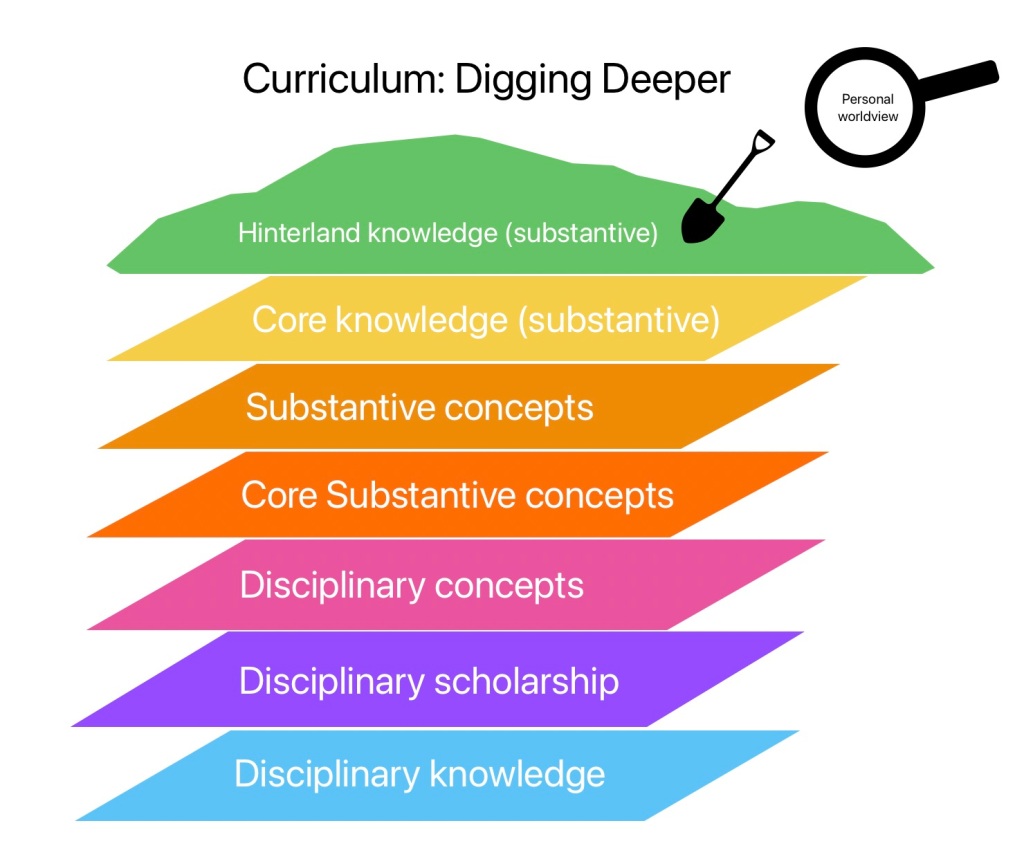

It is possible for an RE curriculum to just be formed of core knowledge or core and hinterland, without any of the other things that my following blogs are going to cover. ‘Just’ getting students to know things is what I think people that criticise ‘knowledge-rich’ approaches. It becomes a collection of pub quiz answers. This is what a lot of RE has done in the past and some schools still do; they don’t dig deeper! The point of this series is to emphasise the importance of knowledge as part of the whole. It cannot stand alone but it is important to consider its part in the curriculum. Hence, this blog series to explore what else makes a good curriculum.

We also know that RE has a high level of teachers with other specialisms. Subject specialists will have the subject knowledge needed to use appropriate hinterland when needed, often spontaneously. However, non-specialists won’t. This is why it is important for schemes of learning to be specific as to the core and the hinterland to be used, and for any CPD time to be used to discuss how these work together.

In my experience, the use of carefully chosen hinterland is a key component of giving students depth of knowledge to apply in different contexts (as illustrated in the story of the adulterous woman above). I think this helps students to be able to synthesise and apply their knowledge much more, for example in GCSE extended writing answers. Students are required to write a short essay using reasoning to support views and to evaluate. I’ve found that the more I give students throughout the course that can be used in these answers, the more they have to select from in their memory to add to the essay. In the past (and I’m sure still, for those that aren’t given enough time) students have been taught ‘set’ answers to questions. I don’t need to do this because I have immersed students in so much knowledge, they have a wide pool to choose from, meaning their answers are much better constructed.

Summary

- We need to be clear what the core and hinterland is for a topic especially for teachers with other specialisms

- We need to ensure that students remember the right stuff

- We need to consider how this knowledge plays its part in our curriculum – when will it be revisited? how do topics link?

Other blogs on core/hinterland

https://achemicalorthodoxy.co.uk/2019/02/01/core-and-hinterland-whats-what-and-why-it-matters/

https://blog.optimus-education.com/what-you-don’t-know-you-don’t-know