The DfE data on absence isn’t a happy read. With persistent absence at 20% for the academic year so far, it’s clear that we are dealing with an issue that there are no silver bullets for. It’s a long term issue for schools which is a consequence of lock downs and the resulting increase in anxiety and depression. So what can we do at a lesson/teacher level to try to help students that are affected. We need to do something!

I’m proposing three strategies that might help. However, these ideas are not really for school refusers, these are for those students that we see once in a while. They’re in for one lesson and then you don’t see them again for a few weeks. Also, they may be subject appropriate strategies. For RE, when we see them so infrequently this has led to a huge improvement in engagement for these students.

Lesson division

I see many people plan their schemes by lesson. So each lesson covers a topic within a scheme. For example when teaching the five pillars of Islam, they might do one lesson on each pillar so five lessons in total. The problem with this is if I’ve missed the first two pillars and I’m in lesson three, I won’t have any idea about those pillars (except through the starter – see below). So I don’t teach ‘by lesson’, I teach by topic across lessons.

Here are some simple illustrations to help visualise my point….

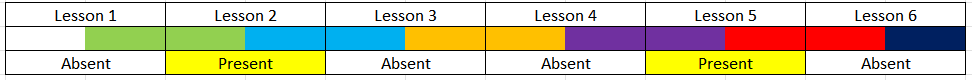

The diagram above shows how many teachers teach. Each lesson covers a topic or area and then the content is ‘done’ (aside from retrieval/revision etc). A student that attends two lessons in six will only have exposure to two topics.

This diagram shows how if you split topics across lessons, a student will be exposed to four different topics. This is a simplistic version of what I actually do (topics don’t all fit neatly into two half lessons!) but hopefully illustrates the point.

You could argue that the four topics they experience won’t be in-depth but I’d rather these students hear some of the content and hearing the key terms being used than two ‘whole’. They will end up with some notes on four topics rather than full notes on two.

When I start the lesson we always do a re-cap of the last lesson so all students can get back into things. This places the learning into context for the absent student and they can see last lesson’s notes on the screen via my visualiser.

Repeated content in starters

I use starter quizzes for a multitude of reasons. In this context they’re used to expose students to previous content. They won’t know the answers when they’re back in lesson but we repeat the quiz questions every lesson, so even if they missed the content teaching, they can pick up on things.

For example, at the start of the topic on Hindus teachings on life after death we talk about the story of Krishna and Arjuna being on a battlefield when discussing issues of life and death. This is important contextual information for the teachings. For the following lessons, I ask the starter question ‘Where were Arjuna and Krishna when they had the conversation?’ After a few lessons, students that weren’t in the initial lesson know it was on a battlefield because we repeatedly reference it. Also, because I don’t just go through the answers but repeat the content (showing the appropriate images/text that I used when I initially taught it) when we mark the starters, the students get exposure to more previous (missed) content. It takes longer than just reeling off the answers but the starter isn’t a pub quiz; it’s retrieval and foundations for the coming lesson. I’ve written before how my starter quizzes take a while. This is why!

Long term enquiry questions

This solution is probably more for humanities subjects where a topic can take longer than one lesson, but might be doable for a topic that has component parts in other subjects i.e. is not cumulative.

We have an overarching enquiry question that lasts any time from half a term or longer which has many different approaches to the answer. Every lesson covers one or more elements, contributing to the answer. A student can pick up where we are in any lesson because there is new material which is linked to past material but doesn’t necessarily rely on it. We have to repeat/summarise previous content to link it with the new, so essential content is presented to them. Whilst this won’t be as in depth as the previous teaching, it gives them a basis to pin new learning.

This really comes into play when we answer the enquiry question. A student can have missed a few lessons but can still answer the question from the two lessons they attended because in those two lessons they have two possible answers to the question.

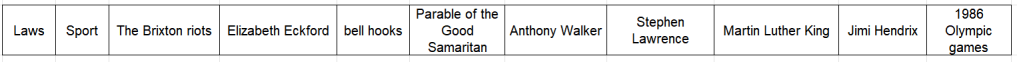

An example for core key stage four is ‘How have people responded to discrimination and was it effective?’. Each lesson looks at case studies of discrimination and the response of those that have been discriminated against. Students that attend all lessons will have 10 case studies to draw from (see below) that have been spread across lessons (not one per lesson).

Even if a student attends the final lesson we will have done at least one case study before they answer it. It’s a limited answer but not a situation of ‘I wasn’t here so I don’t know what to write’. They always have something. This strategy also promotes ‘going deeper’ into a topic rather than rattling through superficially.

These three strategies mean that I don’t have students sitting wasting even more time in class saying ‘ I don’t know about this’ or when it is summative assessment time, not being able to write anything. They’ve made a real difference to my students that I don’t see very often but equally the strategies are good for all students in embedding learning.