I’ve blogged before on how I dislike people talking about groups of children in sweeping generalisations. Pupil premium is a special case as it attracts money. Money makes people do odd things. One thing that seems to have been suggested by someone and then spread throughout schools is marking pupil premium books first.

I personally find the premise behind this ‘strategy’ at best misguided and illogical and at worst discriminatory and unprofessional.

The premise/s they have used to support it are:

Mark PP student books first because you will:

- Be more awake

- The lesson will be more fresh in your mind

- Focus more on them than non-PP

- Spend more time on them

- Give more detailed feedback

- It will be your ‘best’ marking

- You will have a better attention span

- It keeps vulnerable students in your mind

The DfE states that:

PPG provides funding for two policies:

- raising the attainment of disadvantaged pupils of all abilities to reach their potential

- supporting children and young people with parents in the regular armed forces

However there are so many issues surrounding the strategy of marking PP (especially FSM students) books first:

Issue 1- Conflation with academic ability

In many cases PP is conflated with ‘low ability’ or not ‘making progress’. It’s used as a piece of data that indicates academic skills, like you might use a SAT score. This is a huge misuse of data. In no way does PP indicate a child’s academic ability. There will be PP children that have low levels literacy or an SEN need or high absence. Equally there will be PP children that have beyond age reading ability, are classed as ‘above average’ ability and who attend school 100%. You cannot make a sweeping generalisation. If the former is true, marking their books first WILL NOT make any difference.

Issue 2- What about non-PP?

If you are willing to say you mark PP books first so they get better treatment you are essentially saying that non-PP are not worth better treatment. Could you really tell a non-PP child’s parent at parents evening ‘I mark your child’s book last because you’ve never claimed for free school meals’? The value judgment you are making on non-PP is never what the government intended with this funding.

Issue 3 – Who says that the first books marked are the ‘best’? Evidence?

I’ve heard people claim they’re less tired, they are more focussed and they have more time for the first books. This is a very concerning indictment of that teacher/schools marking policy or systems if a teacher publicly says they don’t mark in a similar standard throughout.

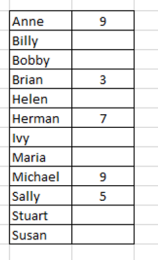

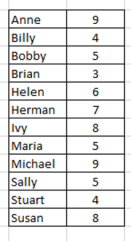

In an unscientific poll on twitter about which books do people mark first, many claim that the first books aren’t always the ‘easiest’ to mark or may not have the ‘best marking’. Teachers need to read a few books to gauge where the class has struggled etc either way, there’s something wrong with choosing PP books to be at the ‘optimum’ stages of marking about other students.

This clearly shows that marking & feedback in schools needs a serious overhaul or complete rethink.

Issue 4 – The child whose parent/s haven’t claimed FSM but could

If you claim that PP children need more attention as they are disadvantaged and need more support you are on really dodgy ground if you have children in your school who fit the criteria but for some reason their parent hasn’t claimed FSM. You are essentially saying, because your parent hasn’t completed a form, I’m not going to give you the attention you may need. That’s immoral and unjust. Judging a student by PP and not by need in my eyes is negligent and unprofessional.

Dr Rebecca Allen, Director, Education Data Lab

points out:

“…it is important to note that many non-FSM pupils come from lower income households than FSM pupils. (Hobbs and Vignoles12 estimate that only around one-quarter to one-half of FSM pupils are in the lowest income households in 2004/5.) This is principally because the very act of receiving means-tested benefits and tax credits pushes children eligible for FSM up the household income distribution. It is the diverse nature of the non-FSM pupils across England that means that is more difficult than we might think to compare pupil premium gaps across schools. A school may substantially narrow the gap by working hard to improve the attainment of their most deprived children, or through the accident of the characteristics of their ineligible children.”

Issue 5 – Evidence it ‘makes a difference’

If any teacher claims that marking PP books first has made a significant difference to a student’s progress I would argue this is the case because:

- It may have ‘closed the gap’ because you’ve ignored non-PP.

- You’ve used effective marking strategies in those books but not in the others, being PP is irrelevant

- You’ve consciously ‘not bothered’ with detailed feedback for non-PP

None of these are admirable.

In a publication of ‘good practice’ from the DfE (thank goodness) none of the methods for minimising barriers include marking PP books first..

The reality of there is very little evidence on what makes effective marking and what improves progress. I’m doubtful that these teachers have found an effective solution that the EEF didn’t see.

Issue 6 – Focussing on the ‘gap’ instead of attainment

When asked about marking PP books first, some teachers have replied with an excellently ‘on message’ response about national statistics showing that we need to ‘close the gap’. All very admirable and I’m sure would be perfect for an interview response. However the reality is that if you focus on the gap the whole time you’re missing the point.

Dr Allen says:

“Concentrate on better results for pupil premium children, rather than narrowing the gap

. Free school meals children are clearly different from one another, but they vary far less than the group who are not eligible for free school meals, since this group includes both those with bankers and cleaners as parents. Many schools have always had pupil premium gaps close to zero because their non-claiming pupils are no different in their social or educational background to their pupil premium children. So, although it is gaps in achievement that contribute to social class inequalities and should be the national benchmark to assessing policy success, it is better for schools to concentrate their focus on the attainment of their FSM pupils rather than the size of their own pupil premium gap.”

Issue 6 – The assumption of PP minority groups

In some schools/classes, non-PP is the minority. Marking PP ‘first’ becomes a challenge as if you believe your marking is ‘best’ with the first few books, which PP books will you put at the top? Another sub group? This truly illustrates how marking PP books first is nonsense.

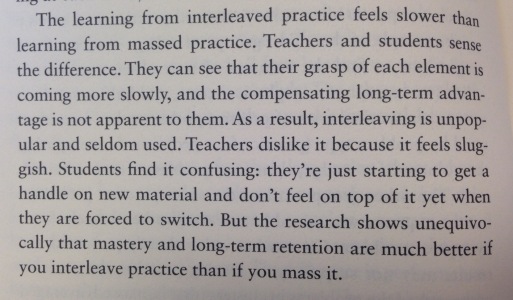

Issue 7 – Misapplication of ‘what works’

Some teachers will argue that they’ve used the EEF toolkit as evidence of ‘what works’ for their PP students. I agree that great feedback and response is essential for learning. The issue is that it’s being justified for use just for PP students. What works for PP students works for everyone. Good teaching is good teaching for all. All students deserve quality feedback. If a teacher cannot equally spread that amongst their students the teacher and/or school need to rethink what they’re policy or system demands.

Dr Allen confirms:

“As it turns out, great schools tend to be great schools for all children in the school – the statistical correlation between who does well for FSM children and who does well for non- FSM children is very high. Moreover, schools can make a difference to the life chances of FSM children – there are huge differences in attainment for these children across schools, far larger than there are for children from wealthy backgrounds who do pretty well in all schools.”

The nFER report on disadvantage makes it very clear is that what works is for all students:

Issue 8- Assuming PP means ‘disadvantaged’

One of the biggest things that annoys me about some teachers attitude to PP students is the assumption that they are disadvantaged. I can’t help feeling that this stereotypical response is what causes the ‘gap’ in the first place. Whether they are disadvantaged or not it is highly unlikely that marking their book first will deal with any disadvantage they do have.

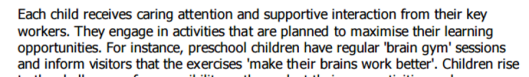

Issue 9 – Lack of focus on the individual child

Finally, the clumping of PP students has almost become a differentiation strategy in itself. It is absolutely not. Within that group of students there are individuals. Each with strengths and needs. Marking their books first seems to be a proxy for meeting their needs. I know the teachers/schools that mark their books first do many other things but I would argue we should mark all books equally and spend that ‘extra’ time with those that are struggling or not making progress, PP or non-PP.

Some teachers and schools have somehow got caught up in a rhetoric surrounding PP students. I teach so that ALL my students can make great progress whilst looking at each student individually for how I can support them. A policy of marking their books first, in my opinion, is a policy made to ‘tick’ a pupil premium action box. How many of these teachers/schools will ditch this method if Ofsted stopped focussing on pp students?

Instead we should be focussing on great teaching (and feedback) for all students.

References & related documents

Click to access Funding-for-disadvantaged-pupils.pdf

Click to access Pupil-Premium-Summit-Report-FINAL-EDIT.pdf

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-pupil-premium-how-schools-are-spending-the-funding-successfully

Click to access DFE-RR411_Supporting_the_attainment_of_disadvantaged_pupils.pdf

Click to access EEF_Marking_Review_April_2016.pdf