This blog aims to outline some of the current challenges that teachers and leaders are dealing with, for those that don’t know what is happening in schools. I’ve tried to back most points with evidence (varying sources) but some of it is anecdotal. It is in no way supposed to be critical of schools and their staff. It’s an overview of where I think we are and why. You may well disagree but unless you spend a significant time in schools then you may not be aware of these things. I come from a secondary background however I suspect these issues are across phases.

The original title of the blog was going to be ‘COVID kids – the impact on schools and children’ which reflects my thoughts on one of the biggest causes of the issues below. They always existed but I believe that the lock-downs of 2020 and 2021 were hugely impactful to children, their parents and ultimately to schools.

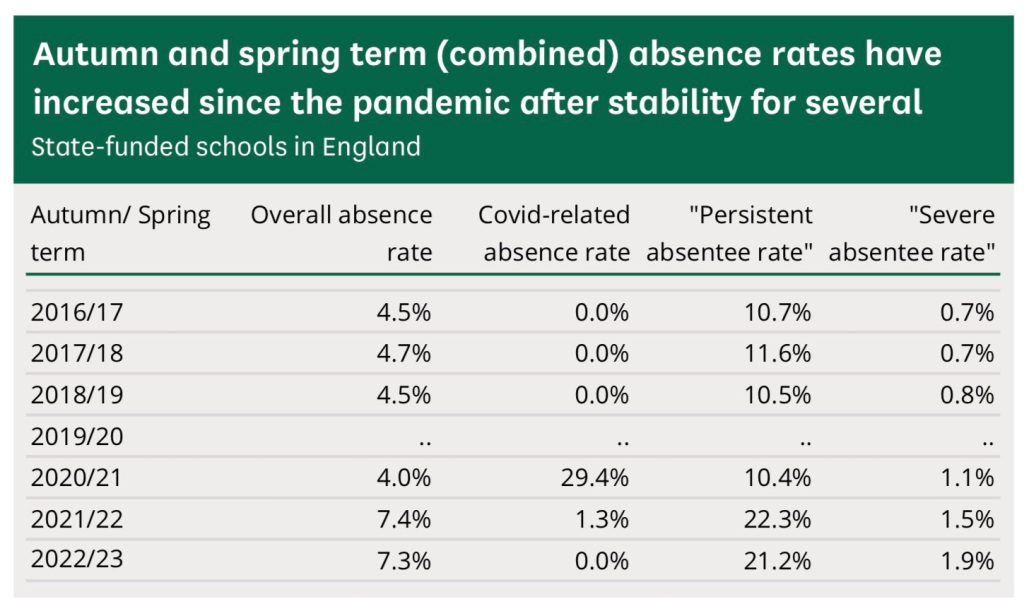

Attendance

Attendance of students is at a stage that I have never experienced in my career. A significant number of students are not coming to school; some coming in less and some not coming in at all.

The evidence of what we can do to deal with this is sparse. We are all trying to come up with things that might make a difference. But it is huge. For many schools, relying on tutors or heads of year to deal with absenteeism is now unmanageable. Schools need to make roles for colleagues to work specifically (and only) with these students and families. But this isn’t enough, reports show that adverts for these sorts of jobs are increasing, but are vacancies being filled? I’ve seen people share threads on X/Twitter of what they’re doing which is lovely to share but I think we should be clear that this isn’t a case of a few ‘hacks’. This needs a coherent strategy at a national level, fully funded and with shared resourcing in what might work. We need people to see this job as rewarding, valued, fully supported with continuous training and do-able. At the moment there is evidence that these jobs are not retaining staff due to “the “emotional intensity” of the work, high workload and frustration with the approach and scope of the work”.

Upping the fine for absence just isn’t going to cut it. Someone that has gone on holiday during term time will have saved multiple times more money than the fine, by avoiding school holiday hiked up prices. And for those whose absence is linked to school refusal, a fine isn’t going to do anything to help. Parents won’t be helped in getting their child to school, by paying an £80 fine.

Parents need help with parenting. They need support in dealing their child that is refusing to get out of bed in the morning or refuses to go into school. However this has fallen onto schools and we don’t have the capacity to do so. We have become an emergency service, social services and pseudo-parents and we just don’t have the knowledge, skills, time or capacity to fulfil these roles. The government needs to deal with this at the root; with current and new parents. I don’t know much about Sure Start but I hear that this sort of programme can have impact (and lo! the evidence for this has appeared today). The government needs huge investment into these sorts of programmes to ensure that future parents can be supported and schools can get back to fulfilling their usual role in society (mainly education).

Behaviour

How people in society behave has changed since the lockdowns. Reports of 50% increase in violence towards shop workers and data showing that violence towards teachers in school has increased, shows that boundaries have shifted.

What training have teachers had for dealing with deep rooted behaviour issues? I feel that dealing with students with more complex issues are way beyond our capabilities. Schools need to be able to support these students where possible but also, where necessary, find students an alternative to their current context, ideally to more specialist provision. There has been funding for more EBD schools however these are way behind their estimated opening time of September 2026.

Persistent disruptive behaviour has increased and schools are having to make the ultimate decision to suspend students. Despite what some think, this isn’t an overnight decision and takes a lot of time and resources to try to resolve before suspension.

The Mental Health crisis

I don’t think we will ever fully know the impact that COVID has had on the nation and the world’s mental health. And when we start to realise the long term impact, it will be too late for intervention for some people.

As already mentioned, teachers and school staff are not trained to deal with the levels of mental health issues we are facing. Coming up with a code for school registers might help in identifying the numbers we face however it’s not a solution. Schools need specific, targeted support for these students because the current systems aren’t coping. CAMHS referrals have significantly increased and the system doesn’t have the capacity to deal with them. Stories are being shared of having to wait weeks for referrals to be processed. This falls back onto school staff that aren’t equipped to deal with the level and complexity of need.

Value of schooling

Unfortunately, during the lockdowns some people broke the law and people in authority have since been found to have not followed the rules that they were enforcing. People’s view of authority figures have been affected by this, this includes schools and school staff. The value of schools has therefore changed in some people’s eyes.

Let’s be brutal, there are students that were told to leave school in March 2020, that now have qualifications that they weren’t fully assessed for. In some cases, students left with grades which may not correlate with what they would have got if they had been assessed in the normal way. They did not experience the end of school rites of passage. They missed out on important life skills and social interactions. These students may become parents themselves soon and I think this will impact their perception of schools and schooling, and consequently their own children.

Some have said that the ‘social contract’ between schools and parents has shifted. Ex-Ofsted Chief inspector Amanda Spielman has said:

“And in education we have seen a troubling shift in attitudes since the pandemic. The social contract that has long bound parents and schools together has been damaged. This unwritten agreement sees parents get their children to school every day and respect the school’s policies and approach. In return, schools give children a good education and help prepare them for their next steps in life. It took years to build and consolidate, from when schooling first became compulsory.

Unfortunately, there is ample evidence that this contract has been fractured, both in absenteeism and in behaviour. Restoring this contract is vital to sustaining post-pandemic progress, but is likely to take years to rebuild fully.”

This links to socialisation.

Socialisation

I’m not an expert but I can see the impact that lock downs have had on students’ socialisation. Surveys seem to support the impact that they had on social and emotional development. For some children, in their formative years, they didn’t have to deal with people they didn’t like or do what they didn’t want to do, for several months. I think that some students haven’t developed the skills of dealing with these important aspects of life. Some are using ‘fight or flight’ when encountering things they don’t like. Flight includes not coming to school and internal truancy. Fight includes refusing to go to class and arguing with staff.

Starting secondary school is a hugely important time for deciding who you are, how you are going to be and who you are going to hang about with. School provides children with the space to be with other people. People their own age, people that are younger and then some people that are a lot older! Part of being in school is learning to get on with people you may like but also people you may not like. Also, it’s doing some things you might like but also doing things you might not like. Many students missed out on these important stepping stones in life. (I believe that current year 10 have had the worst of this. They missed their year 6 SATs, end of primary school rites of passage and couldn’t have the same induction to secondary school as normal. They then went into lock down again in term 2 and had barely found their feet in year 7.)

The medical profession is also noticing this and its impact on relationships:

“The COVID-19 crisis highlights that school fulfils not only an educational mission of knowledge acquisition, but it also satisfies the socialisation needs of young people. With students at home, the school community is absent and despite the virtual interactions and learning opportunities provided by the internet and social networks, a barrier is created in the educational relationship between pupils and teachers.“

Parents

It’s impossible to fully quantify what parents went through during lockdowns. Some parents went from being mum/dad to also being learning mentor or even teacher. They were handed responsibility for ensuring their child did things that they wouldn’t usually have to do. Many found maintaining discipline and keeping their child/ren motivated, hard.

Schools are now reporting an increase in parents challenging school rules. Whilst people will always debate which rules should/shouldn’t be challenged it’s the impact that these challenges have on teacher and school leaders that goes unrecorded. Receiving abusive emails from parents, parents shouting at teachers at the school gate or posting hateful posts on social media about staff, have an impact. Some have forgotten they are dealing with human beings and that schools aren’t the enemy.

Sadly, parents questioning authority of the school has an impact on students. If they’re hearing ‘I’ll go up the school and tell them…..’ then this is giving a message to children about who is ‘in charge’. Students then openly question teachers when they are told things they don’t want to do/hear. They are copying what their parents are saying at home. Whilst students are in school they are required to follow school rules for their own and others’ safety. This crossing of boundaries was not helped when school was home, and parents became their authority on school work. The boundaries of authority became blurred.

Both schools and Ofsted have received significantly more complaints post COVID. These are taking up Headteachers’ time. Some aren’t warranted so are wasting time that could be spent on supporting students. It’s also not good for Headteacher well being. All credit to Headteachers that deal with these on a daily basis however it is a huge time-consumer and I can’t help feeling it is also changing the nature of the job.

Cost of living, poverty and disadvantage

Reports show that there is an increase in poverty. What does this mean for schools?

Disadvantage is often highlighted in education data regarding the issues above. For example, the new fine system will likely affect the disadvantaged at secondary more. Similarly for attendance, the gap between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged has increased.

The pressure then falls upon teachers to try to ‘close’ the gap. This is now becoming a complete nonsensical thing to expect from teachers. The issues of disadvantage are far more complex than an engaging lesson or after school class can resolve. Amongst other things, the Education Policy Institute recommend a cross-party child poverty strategy.

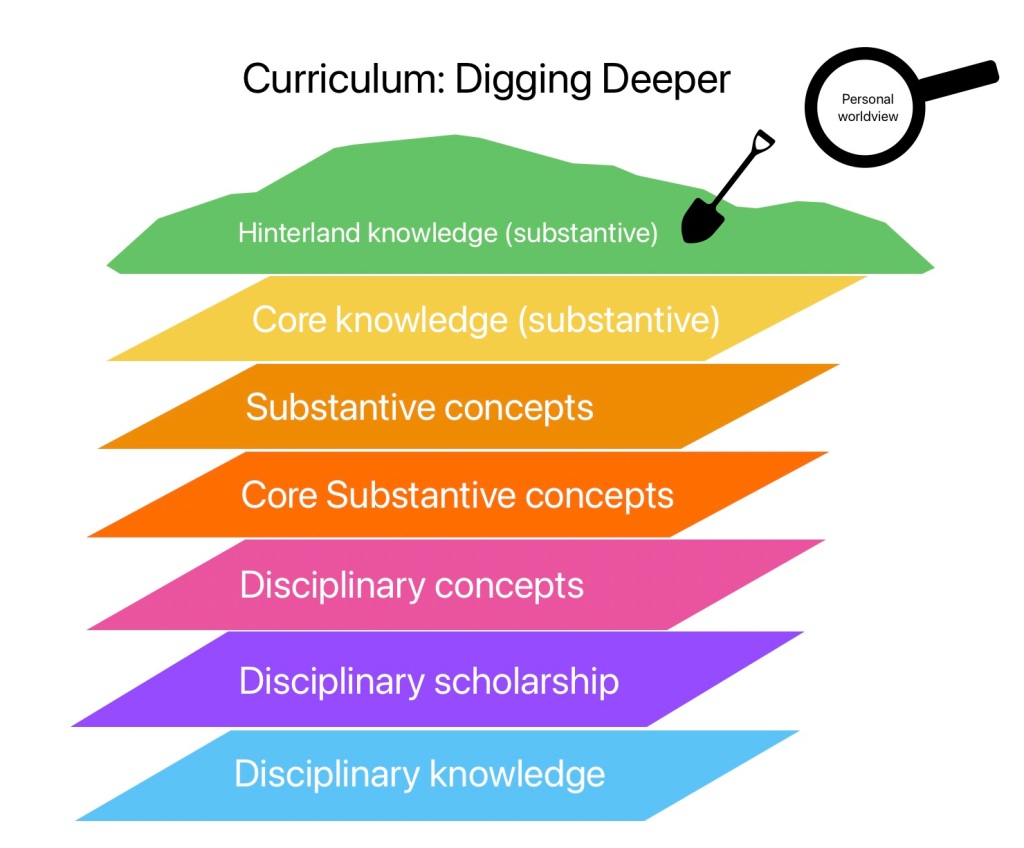

Teachers, teaching and learning

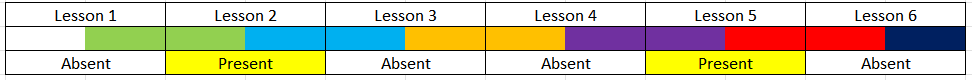

Anecdotally, more and more discussions about education are about the above issues and less about teaching and learning. Teachers don’t have time to talk about curriculum matters if they’re dealing with behaviour matters. Form tutors won’t have time to talk to students about learning if they’re talking about attendance. We’re losing the time and energy to talk about the stuff that matters to deal with things that will probably make a limited difference.

Even back when the lock downs were happening, teachers could see that COVID was going to cause issues with learning. If it didn’t, we’d have some big questions to ask about the role of schools!

More recent research suggests the impact of lock-downs on learning. One report found there were less children who achieved a ‘Good Level of Development’ and the perception from parents and schools is that children (EYFS/KS1) have been disadvantaged in their socio-emotional wellbeing, language and numeracy skills.

The Dfe summarised suggestions of what aspects of learning have had the most losses:

Teachers aren’t as happy as they have been. They’re now dealing with everything above. Teachers are increasingly stressed and their wellbeing has hit a 5 year low. Whilst the government has promised a “£1.5 million of new investment to deliver a three-year mental health and wellbeing support package for school and college leaders; providing professional supervision and counselling to at least 2,500 leaders”. However this doesn’t help with teacher retention.

Teachers are now less inclined to recommend teaching as a career to others and this has significantly changed over the past three years.

To top this all off, education is having a recruitment and retention crisis. So even if we get children into schools it is becoming less and less likely they’ll have a specialist or even a regular member of staff teaching them. The quality of education cannot be the same with non-specialist or supply staff, than with regular, subject specialists. There is also a shortage of supply teachers so internal staff are having to increasingly cover for colleagues. This is not good for teacher wellbeing and will clearly impact retention. Why bother going to school if school isn’t fully functioning as it should?

The reality is that four years ago, schools stopped functioning in the way they had been, for the majority of students. Whilst there may be doubts over correlation or causation, I believe that the impact of the pandemic, in particular the lockdowns have significantly affected schools, children and parents. Is COVID’s impact on education the canary in the mine? As these children grow up, what further impact will there be on society? The data is piling up but it seems the solutions (or at least possible strategies to try) are not so forthcoming, at least at a governmental level. Society has changed, never to be the same again. As a new government is on the horizon, I hope they take on board all these issues. We need new direction and support. Schools need help with this ‘new normal’.

(NB I never usually write anything political and expect I will delete soon after publishing.)